School Speak Oracy

I was sent a link to an ongoing discussion on Twitter about the ethics of teaching children who do not speak in Standard English to do so. There are clearly many people who feel great sensitivity around this area – and that is totally understandable.

One of the schools I work most closely with is in an area of massive deprivation, with almost the entire pupil body speaking either in strong Yorkshire accents or with cultural ones. Their teachers and support staff, most of whom also speak with regional accents (although less than half the teachers are from Yorkshire, while all the support staff are from the locality of the school) have embraced the necessities of children learning to speak in the standardised form of English. They have long used my maxim: ‘If a child can’t say it, a child can’t write it,’ and this is now modified to:

‘If a child can’t say it in Standard English, a child can’t write it in Standard English.’

Children must learn to speak confidently and articulately in Standard English if they are to think in the standard form and therefore write, proof and edit in it, but this does NOT mean that they can no longer enjoy and celebrate their own local accent.

The risk of offence or humiliation for children in learning Standard English is not the ‘what’ but the ‘how’. By including the standardised form of English as one of the ‘codes of speech’ pupils will hear around them in their lives – whether in shops, in restaurants, on streets, on transport, on television or on other media – and teaching children to respect all these forms of speech, the stigmas are removed and the elitism is eradicated. We then teach them to switch easily between forms (this is called code switching) whilst having fun – often through role play and performance – and with practice this becomes a smooth transition from their own home accent into other forms of their choice for purpose, but always including models that are entirely in Standard English.

Sadly, some in the profession have not yet understood that Standard English may still be spoken with a regional accent – it purely means that all grammar and pronunciation will be accurate. Where alternative grammatical and vocabulary forms exist that are not in the accepted standard form, speech becomes a dialect (again, a wonderful thing to be celebrated. I love Yorkshire dialects).

Included in the children’s increased repertoire of readily-available forms of speech, however, will also be ‘received pronunciation’ – or the accent of many of the highly educated or the wealthy – formerly known as ‘BBC English’. This is treated purely as another code of speech in their repertoire, and children will use it in role play, drama and presentations in the same way as they will use other codes. We have renamed this code ‘School Speak’ in our oracy programme, and encourage schools to modify that to the name of the school (for example, Roundwood Speak) if they so choose.

Thus, we make ‘School Speak’ an inclusive form that every child and adult in the school will use when asked – whether as the sustained form of speech for all throughout one or more entire lessons a day, or for specific purposes such as a debate, a performance (for example, of poetry) or as a particular character in role play. ALL children sharing the same speech form for the same purposes at the same time… equality with mutual respect – and then all children reverting to the daily speech code of their choice… again, equality with mutual respect!

I have just enjoyed writing a short book for publication as a PDF to help schools to launch and support development of powerful oratory in their schools with dignity. This very affordable book will include resources to support teachers and pupils in developing their exciting and highly entertaining orations for school gatherings and celebrations. More information will be available on our website soon.

Through this means of embedding School Speak in fun and dramatic performances, children will find, as time progresses, that switching from their daily voice, local accent or ‘street talk’ into an impressive form of oratory when appropriate, to be a natural and rewarding experience that will support them in their life as they represent their class, their school and their family, as they attend interviews and as they interact with people of other speech forms in the wider world.

There is no shame in this achievement – only joy and celebration of choice and flexibility. Where else will children develop this empowering and life-changing skill? The clue is in the name – ‘teachers’. We are the teachers, we should empower and enable without being made to feel shame or derision.

Only a week or so ago, a secondary teacher tweeted explaining how he modelled speaking in modified standard English, using sophisticated features and in expressive tones of respect and oration when speaking to all his students in school, and how so many were beginning to reply in a similar vein, modifying their local ‘street talk’ without the need for judgmental comment or potentially humiliating teaching. I wonder, sometimes, whether all our secondary colleagues – who we value so highly – are aware of how hard we work to prepare our pupils for secondary education?

We TEACH them…

…and so often a challenging aspect of learning in one phase of education later becomes a revisit – reawakening memories that are deep seated in the sub-conscious and enabling them to be refreshed, extended and invigorated with the maturity of the years and giving the impression of an ease of learning that belies the hard work of the previous phases.

Never feel shame about teaching children something that could potentially enrich and reform their life opportunities, for we all know that TEACHERS MAKE THE DIFFERENCE.

Talk:Write

A fun and flexible approach to improving children’s vocabulary, speech, and writing.

Oracy Is Not Just Speaking and Listening

I visit schools who are doing ‘oracy’ and I see speaking and listening! Mind you – I am so pleased to see children conversing and teachers asking a wealth of interesting questions – but it ain’t oracy. Speaking and listening is valuable; oracy is valuable – they overlap and have elements in common – but they are different. It remains confusing because, inevitably, you see and hear one in the other and vice versa and often the boundaries are very blurred.

So, what IS oracy and how do I know what it isn’t when so many great teachers and leaders think they are ‘doing’ it? Well, to be fair it has taken me over two years and a lot of hard work to come up with an answer that may solve that mystery.

You see, Andrew Wilkinson did not know the answer himself when he came up with the terminology in 1965. How can you create a new ‘something’ to teach children when you do not yet know what the ‘something’ is? It is important to be able to define your vision before you attempt to communicate it to others. That is why new thinking and new ideas often have slow and shaky starts until the definition is crystal.

Wilkinson’s aspiration was good, however, he wanted to raise the profile of talk and language so that it was NOT just speaking and listening. He created the name ‘oracy’ to put his new aspiration on a par with numeracy and literacy and he developed a massive and much underrated national initiative to promote it, but he still didn’t know what it was and neither did most of the country.

There is so much written about the cruciality of oracy, and I have read much of it, but nowhere do you truly understand what it means. Voice 21 has established itself as an authority, saying;

We believe that schools have the power to change a child’s life and create a fairer society. We support schools to build oracy into learning, the curriculum and wider school life. Oracy is the ability to speak and listen in a range of different contexts – one-to-one, in groups and to a larger audience. Oracy skills set children up for success in school and life.

So what is it? Well, perhaps Voice 21 is close to defining ‘oracy’ when it tells you what you will see and hear in schools they work with:

In Voice 21 schools, you will hear students solving problems collaboratively in maths and dissecting arguments in history, talking through conflicts in the playground and leading assemblies.

So close to a definition – but not! Was Andrew Wilkinson influenced by Sir Evelyn Wrench when the latter said that effective discussion and communication had four components:

- reasoning and evidence;

- organisation and presentation;

- listening and response;

- expression and delivery.

Wrench, a former journalist, had seen his original international communication organisations morph into the promotion of discussion and communication between young people around the world in order that they might better understand each other and show mutual respect by the mid-1960s, before he died.

Wrench (1882 to 1966) saw international co-operation and communication as crucial for world peace and his summary of the four components for his aspirations possibly reflect the aims of Voice 21:

Voice 21 sets out four strands of oracy – Physical, Linguistic, Cognitive and Social and Emotional. The ‘physical’ includes elements such as voice projection, using eye contact and gesture. ‘Linguistic’ involves using appropriate vocabulary and choosing the right language for different occasions; ‘cognitive’ is about organising the content of your speech and ‘social and emotional ’ includes working with others, taking turns and developing confidence in speaking.

Ah, now it is becoming clearer. In identifying the four components of communication promoted through his work, he was embracing the best of speaking and listening – a best that verges on oracy and sometimes becomes it.

Wilkinson’s aspirations for the National Oracy Project (1987 to 1993) were established as a key contribution to the early National Curriculum. However, Wilkinson himself struggled to define the term – eventually coming up with a statement he immediately felt was inadequate for the job. In his own words, Wilkinson said that oracy was;

…the verbalisation of experience.

As he promptly acknowledged his dissatisfaction with this, a colleague suggested that perhaps it was rather;

…the experience of verbalisation…

whereupon Wilkinson seized the diametric and married the two. I read them, I understood them, but I knew not what they meant.

I was extremely fortunate to be invited to participate in the Bradford strand of the National Oracy Project upon my return to the United Kingdom in 1986 after 17 years in the Caribbean. I had no training, no induction or introduction, no materials and attended no meetings but I much enjoyed working with my 13-year-old Middle School pupils on communication skills and we all developed a passion for the huge effectiveness of talk, debate and discussion on our studies. We ‘did’ speaking and listening in the best sense of the word. We talked endlessly about the power of talk and the role inspirational discussion plays in understanding learning, clarifying it, embedding it and moving it forward.

We benefit so hugely from the first three elements of Wrench’s description, but we do not often – in the busy overloaded world of education in England – move through to that final stage…

For the past two years I have studied, reflected on and written about oracy, and finally I feel my understanding reflects Wilkinson’s diametric. I have watched communication and discussion radically improve in the schools participating in our trials, but the key element is still in development. And then – while enjoying a dramatic performance of a verbalisation of the experience of analysing a response to a mythical image – the penny dropped as the missing word fell into place.

It is an oral performance of an experience, performed with passion and dramatic communication. It takes creativity, skill, rehearsal and interpretation… but oh it is so powerful in its illustration and conveyance of the impact of an experience that must have been 100% understood, absorbed and embraced to be verbalised through oracy.

It is exciting to be on the fringes of the birth of the Oracy Commission:

The Commission on the Future of Oracy Education in England is an independent commission, chaired by Geoff Barton and hosted by Voice 21.

I see with interest that their discussions and contributions follow that same pathway that I have been struggling along with so much joy and enlightenment. Now I have words to express what I was fortunate to have been given by an articulate and inquisitive family at the kitchen table in the days before TV and media – an ability used all my career without ever knowing how to define it. This was not a gift of class but rather a gift of culture. We were genuinely impoverished financially but blessed in ability to use language. Now every child in the country and the world may have the great good fortune to acquire those same skills.

Of course I was unable to define oracy, I was still in the understanding and absorbing phase – as so many others are still today. It is everything both Welch and Wilkinson said and everything Voice 21 has said. You can’t achieve oracy without speaking and listening but you can usefully and productively use speaking and listening in education without taking it on that final, massive-for-many climb into oracy.

Now we know it, let’s get our boots on…

Talk:Write

A fun and flexible approach to improving children’s vocabulary, speech, and writing.

Technical Grammar in Primary

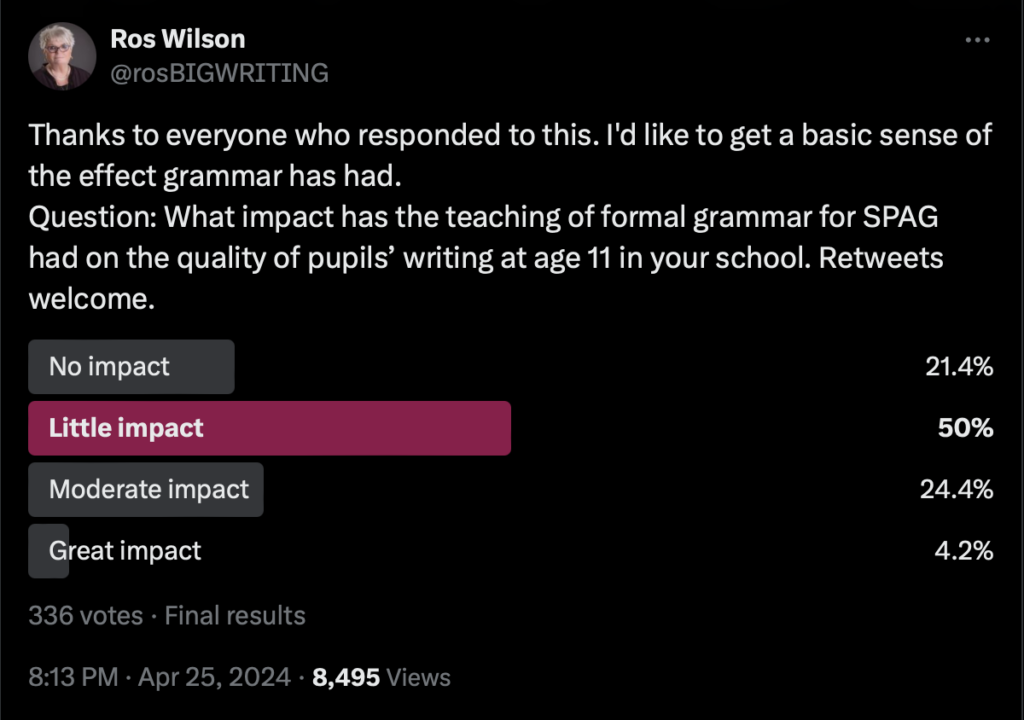

I recently started a Twitter debate about the merits and disadvantages of the formal teaching of technical terminology for grammar. The consensus seemed to be that the only advantages for the teaching of primary aged children were if a school wanted children to perform well in the SPAG tests in Year 6! As ever, there was some advocacy for the benefits for MFL teaching in secondary schools – however, the majority of primary school leaders do not seem to see preparing pupils for success in secondary MFL exams as a priority for primary education.

Over 70% of the colleagues who responded to the poll we circulated on teaching myriad technical grammatical terminology that was included (by statutory requirement) in the revised National Curriculum of 2014 – without consultation – concluded that it had little or no impact on pupils’ writing prowess in Year 6. Indeed, a significant number of comments indicated that writing had lost a lot of its zest and had become more of a technical chore. Over 20% of respondents thought the benefits were minimal to none. One comment noted improvement to understanding rules of punctuation and the others related to later benefits in secondary education.

If children already have a good understanding of more complex grammatical structures and are able to use them effectively in their writing, then the later learning of the formal terminology is made easier and has purpose and meaning. The problem with the grammar requirements imposed is that they require the formal teaching first and then the later explanation of what it means and why a writer might need it. It reminds me strongly of the textbooks we used for learning grammar when I was at secondary school back in the 1950s.

Thinking of these led me to google grammar textbooks of the 1950s and to my surprise the search picked up on grammar today, and the first items identified were all blogs or similar by esteemed writers or educators criticising the imposition of the technical grammar for SPAG.

Michael Rosen’s blog of March 2016 makes protest about the introduction of SPAG. He provides a sample 11 plus paper from that era and says:

You can see what kind of ‘grammar’ questions we had in the 11 plus exams in the 1950s here. It was limited, as I have said, mostly to using the simplest terms – noun, verb, adjective, adverb… and the simplest stuff on tense. The questions mostly involved ‘filling in the gap’ type, so at least you had the context of that sentence to get it right. I’m not saying that this was ideal either, but it was fairly limited in terms of the amount of time we spent doing it and how much emphasis there was on doing it.

Even so, this was part of the means by which the 1950s system failed at least two-thirds of all children. It is quite unfair of Nick Gibb to claim that this is what’s being ‘brought back’. A much more complex raft of terms and processes are in SPaG and it’s one of the main means by which schools and teachers are being judged.

In ‘The Wrong Way to Teach Grammar’, Rachel Cleary (The Atlantic, 2002) says:

A century of research shows that traditional grammar lessons – those hours spent diagramming sentences and memorizing parts of speech – don’t help and may even hinder students’ efforts to become better writers. Yes, they need to learn grammar, but the old-fashioned way does not work. This finding – confirmed in 1984, 2007, and 2012 through reviews of over 250 studies – is consistent among students of all ages, from elementary school through college. For example, one well-regarded study followed three groups of students from 9th to 11th grade where one group had traditional rule-bound lessons, a second received an alternative approach to grammar instruction, and a third received no grammar lessons at all, just more literature and creative writing. The result: No significant differences among the three groups – except that both grammar groups emerged with a strong antipathy to English.

And Rachel was discussing the impact of formal grammar in secondary schools.

In a desperate urge to be democratic and quote both sides of the argument I then put ‘support for teaching technical grammar at primary school’ into the search engine and the following came up: Teaching Technical Grammar Terms Doesn’t Improve Children’s Writing (Dominic Wyse, Teachwire, 2024). Dominic says:

We now have the benefit of a significant amount of research to inform the ways in which writing can, and perhaps should, be taught. I have recently contributed to this research in two ways. Firstly, I’ve undertaken an analysis of the research evidence on whether the teaching of formal grammar helps writing. Secondly, I’ve also undertaken a four-year study of writing from a range of perspectives including philosophical, historical and empirical research studies addressing writing across the life course… In addition to more than 150 individually specified elements of spelling and five pages of detailed specification of grammar (that are statutory), primary teachers in England are required to teach and assess their pupils’ knowledge of a range of terms, including compounds, suffixes, determiners, cohesion, ambiguity, ellipsis, modal verbs and lots more. It is presumably intended that the learning of these terms will help children to write better because they are included in the programme of study for writing, yet the evidence is clear – traditional grammar teaching does not lead to improvements in children’s writing.

All in all, articles and blogs critical of the NC 2014 grammar requirements far outweigh support for the arbitrary decisions of the then non-educationalist Secretary of State for education and confirm my despair that a succession of changes of leadership has failed to address the lack of judgement in the English curriculum criticised by so many. The degree of detail required by the inclusion of technical terminology for grammar in the 2014 NC is absolutely unnecessary for effective writing by pupils up to fourteen years old and has no impact on communication, creativity or composition. This level of learning is only necessary for those seeking higher level qualifications in the area of linguistics.

I conclude this blog with the wisdom of Simon Kidwell, President NAHT, in his blog, published by Teachwire in 2022:

Since 2014 I have spoken to a senior politician at the DfE and to experts in the field of teaching grammar, and I am yet to meet anyone who believes that the current grammar curriculum for primary schools is fit for purpose or age-appropriate. One teacher, Alison Vaughan, commented: “The overloaded grammar curriculum holds back learning for those with poor working memory and slow processing. These students are already working hard to remember punctuation and spelling… They need more time consolidating the basics, not complex terminology.” My colleague, headteacher Michael Tidd, added: “I think some of it is just pointless at primary level (I’m looking at you, subjunctive form!) and ends up being overly simplistic because of that…” Objections extend beyond the classroom, too, with The Times reporting that the government’s key curriculum adviser, Tim Oates, said that there was a “genuine problem about undue complexity in demand” in the content of 2016’s SPaG test. A lot of the issue, then, is with curricular sequencing, or a lack thereof. The teaching timeline for these complex concepts is out of whack, and we need to reconsider at what point we should be expecting our pupils to understand and absorb them.

Simon Kidwell has worked as a headteacher and school principal for 17 years, and has led three successful primary schools to achieve rapid and sustained improvement.

It is distressing to see political leaders, who appear to be totally lacking in knowledge or understanding about the needs and abilities of pupils in primary education, ignore the wealth of knowledge and opinion expressed by primary leaders and experts. If, as Simon Kidwell intimates, the NAHT is ready and able to take the lead in decision making for education, we may at last see curricular reform that reflects the true principles of education for our pupils. Simon closed the powerful 2024 NAHT Conference with the words; “The solutions to the challenges we have exist in this room.” May our talented heads rise to those challenges and bring stability and strength back to our profession.

Talk:Write

A fun and flexible approach to improving children’s vocabulary, speech, and writing.

Reflections on It Takes 5 Years to Become a Teacher

It is now 4 years since we published ‘It Takes 5 Years to Become a Teacher’, and it is gratifying how popular this little book has become. Besides the main body of my personal biographical experience and myriad advice and tips, there are a significant number of case studies full of the early days of a range of colleagues from all over the country and the world.

Recently, I have so enjoyed dipping back into these case studies, savouring the rich mix of experiences from the first years in the classroom and amusing tales of blunders and mini disasters that never fail to make me chuckle. I shall always be grateful for the plethora of colleagues who so generously contributed their memories of those first years in the profession.

What the writing and compilation of this book shows so clearly is that no amount of university study and brief placement experience can prepare us for the totally unexpected and unpredictable mishaps and moments of bliss that working with children brings. It is that very unpredictability that makes no amount of training, coaching and study able to prevent or adequately prepare us for. Many of us – seemingly well prepared and geared up for this new adventure – found the first weeks ran smoothly with compliant pupils and sweet successes – and then the trials began. Small difficulties and unexpected glitches began to confront us and exposed our naivety, tempting some pupils to test us and seize the opportunity to amuse their peers with antics of a class clown. The worst events, however, were often those that were purely the outcome of our own lack of experience and thus slow or inappropriate reactions.

Teaching is a wonderful career, diverse and different from minute to minute. It is hard to think of another profession where, for six hours a day (seven, but with two short breaks), an individual is unable to sit down and relax, sip a coffee or a coke, nibble a biscuit or suck a sweet or make or answer a quick phone call. Other professions that handle life can snatch a couple of minutes between cases – but not teachers. Save for a short toilet stop at morning play and an average of 20 minutes of the 45 to 60 minute lunch break, we are constantly vigilant, orating, articulating, chattering, conversing, discussing, echoing, enunciating, expressing, pronouncing, ranting, repeating and generally performing – dynamic, dramatic and vigorous.

We are thespians, scientists, astronomers, explorers, researchers and debaters. Does any other profession that is not on the stage wear so many cloaks? Adopt so many roles? It is our privilege to interest and engage, to motivate and excite, to charm and persuade, often with charisma and wit – even when we are exhausted, under the weather or in the midst of some personal crisis in our private life.

Rereading this summary of features of life for those of us with the privilege of working daily in the classroom, I wonder how we do it and how we sustain it day in and day out, in all weathers and throughout all the normal traumas life brings – and particularly how we did it as young and innocent newcomers to the profession. No wonder there were times when we struggled, times when we questioned our abilities and our commitment. And then there was the ever-increasing mountain of paperwork, most of which has no bearing on our daily ability to teach effectively; much of it imposed by those who have never experienced this career we have chosen and have no in-depth knowledge of what we go through day in and day out.

Yet we survive, we battle on and slowly the sun rises and all falls into place and clarity dawns. We are never safe from the unexpected, but our competency to cope and to lift our heads and deal with the day-to-day crises and chaos with confidence and clarity grows and blossoms as we truly become effective and efficient teachers. So, have faith, learn to laugh at yourself and talk endlessly with trusted colleagues, family and friends as you find your way, blossom and grow.

Talk:Write

A fun and flexible approach to improving children’s vocabulary, speech, and writing.

Oracy in Practice

In my last blog I compared the simplistic definitions of oracy found in popular dictionaries – mainly being alternative ways of saying ‘speaking and listening’ – with the impressive analysis of The English-Speaking Union, founded in 1918 by Sir Evelyn Wrench. My summary of these findings, in the first blog, was that these are the skills of research, communication of findings, debate and presentation. THIS is oracy, the ability to not only speak, but to adapt speech, selecting and refining – and ultimately to write if that is the goal – for audience and purpose.

Currently, I am working with a school very close to my heart on the development of oracy. The two newly appointed lead leachers are excited and enthusiastic about the proposed programme for embedding oracy across the school in everything they do. They know that the children’s learning will be so much better, richer and more comprehensible with an oracy driven approach – reflecting authentic ‘talking to learn’ – and that children’s learning will also be more accurately assessable through speech – but they also know that the children’s oracy will itself improve and become the school’s own style of speech, ‘school suave speak’ in constant use throughout every lesson, and this is a school where the majority of the children have a strong Yorkshire accent or dialect, like myself. We are already celebrating that accent in this school, and pupils are having fun code switching between their Standard English, school suave speak and their informal, Yorkshire daily speaking voice. Talk:Write is not about judgement and disparagement, it is about adaptability – having appropriate speech forms for purpose.

In this school, pupils are already using oracy techniques to embed up to three new suave words a week, deploying them successfully in communication both through speech and writing. Further, they are creating short, fun dialogues between characters speaking in different speech forms and are also embedding suave sentence structures for use in presentations – both oral and written. The most recent addition to their portfolio of oracy activities will involve 30 minutes being devoted to each child in the class forming a suave sentence to explain which aspect of learning – in any subject – they found most interesting or exciting each week. They will open the sentence with their own chosen suave opener and include one suave word of their choice from the many suave words they have already embedded in classrooms throughout the school. They will practise their oral delivery with friends and then each will, in turn, deliver their sentence to the class. If anyone wishes to respond, they may raise one finger and then will be invited to do so with an appropriate response, such as: ‘Jonah, I see you wish to comment?’ Tables will usually be arranged in an open horseshoe to facilitate this introduction to the future skills of debate, to be focused on next year.

To this end, each class is being provided with a list of oracy openers for display, to start the process rolling. These include statements like:

- ‘For me, the moment of greatest area of interest this week was…’

- ‘Undoubtedly, the most exciting moment for me this week was….’

- ‘Overall, I feel the most fascinating learning of the week has been…’

- ‘As I think about my learning across this week…’

- ‘I have enjoyed so much of my learning this week, however, I feel that …’

- ‘Despite enjoying almost all my learning this week, one item especially…’

- ‘Although I have thoroughly enjoyed my learning this week, of particular enjoyment was…’

- ‘An outstanding aspect of learning for me this week was…’

- ‘With great difficulty, I have identified learning about XXXXX as the most fascinating…. ‘

And so forth.

Throughout the term, children will be encouraged to experiment with these forms as they produce their weekly comment, restructuring and mixing and matching from the start, in order to personalise them and to widen the range heard and used. In the last week of each term or half term, each child across the school will then select the one they performed that they enjoyed most that term, writing a short paragraph on that learning. They will share this with friends, building in suave features of language, being creative with structures and rehearsing oral presentation through constant re-reading and rehearsal, with some – hopefully – learning from memory. Then each class or year will have a presentation session where every child presents their speech and the one or two voted best to represent their class will go forward to a whole-school performance in assembly.

The following are exemplar steps in the process for Jonah, aged 10:

- His curriculum statement in his class’s contribution to weekly assembly:

‘An outstanding aspect of learning for me this week was our research into the impact of global warming on weather throughout this winter, 2023/24.’ - Jonah then worked with Daisy and Leon to turn this contribution, and each of theirs, into suave speak paragraphs. The following is Jonah’s, but Leon contributed the word ‘engrossing’ for Jonah and Daisy checked the range of suave openers used by Jonah, concluding he had used a good range without overdoing things. The following is Jonah’s finished paragraph:

‘An outstanding aspect of learning for me this week was our research into the impact of global warming on weather throughout this winter, 2023/24. This project commenced with our collecting data on weather patterns throughout the past decade in Yorkshire in winter, using information from The Yorkshire Post and the BBC, besides the local internet weather site. Ultimately, this led to comparisons with data from recording the weather throughout December, January and February, using daily temperature and climactic measures and the internet. All in all, this proved an engrossing piece of research that led us to conclude that our weather had been both far warmer and wetter than the usual winters experienced in my lifetime.’ - At the March year assembly, Jonah performed his paragraph as one of three representatives for his class. He had rehearsed it a total of eight times with his friends and at home with his family, practising his inflection, projection, pronunciation and pace – his class’s agreed targets for school suave speak.

- Although Jonah did not know all his speech by heart at the Easter assembly, he used a modified form for his summer term presentation on the subject of research into the origins of the Yorkshire dialect, his chosen learning from that term, which he performed in late June entirely from memory with no script.

We hope you have enjoyed this snapshot of real-life oracy teaching. I hope to keep a record tracking progress in two very different schools over the coming calendar year, sharing outcomes and ideas as we proceed.

There are now resource sheets on oracy openers which will be available on the website from April.

Talk:Write

A fun and flexible approach to improving children’s vocabulary, speech, and writing.

Oracy: Is that All it Is?

For those of us who were teaching in state school classrooms in 1989 and beyond, the introduction of the original National Curriculum for England came as a total shock. We were in no way prepared for it. We received no helpful training or induction. Colleagues working for Local Authorities appeared to be only a short paragraph ahead of us in their understanding.

As a head of English in a middle school, I naturally focused my initial energies on the curriculum for English, with its three distinct sections; AT1: Speaking and Listening, AT2: Reading and AT3: Writing. I found, as did many others, that the Speaking and Listening said little, expected less and interested no-one. It stood alone, in isolation.

I was, however, extremely fortunate to be invited to take part, with our pupils and staff, in the National Oracy Project – with its wealth of materials and resources – piloted from 1987 to 1993 to support the development of speaking and listening skills. This re-enforced my career-long passion for the priority of oracy in education and pupils’ future lives. However, my move to primary in 1990 to become assessment lead led to my embracing the entire curriculum, except for English AT1.

In 2013, the revised National Curriculum renamed AT1 ‘Spoken Language’ but its introduction still maintained clear separation between the two most integral skills of oracy. I quote:

The quality and variety of language that pupils hear and speak are vital for developing their vocabulary and grammar and their understanding for reading and writing. Teachers should therefore ensure the continual development of pupils’ confidence and competence in spoken language and listening skills.

Is THAT all it is?

This revised English curriculum takes up almost half of the entire National Curriculum for Key Stages 1 and 2 with its 11 intrinsic subjects and 4 associated subjects, and yet – after just over a side on Spoken Language for all of Key Stages 1 and 2 – it is almost entirely devoted to spelling, grammar and punctuation rules. And thus, the National Curriculum has persisted in paying lip-service to the crucial skills of oracy by refusing to acknowledge the need to embed the two skills as one for children’s learning and development.

Indeed, the world of education failed to truly embrace the creation of the concept when it was first developed by Andrew Wilkinson in the 1960s. He created the name ‘oracy’ by analogy from the terms ‘literacy’ and ‘numeracy’.

Wilkinson executed this revolutionary perspective in response to the perceived neglect of the skills of oral communication in education 64 years ago – and it has only recently been discovered by the majority of the world of education in this millennium.

According to Wilkinson’s conceptualization, oracy in educational theory is the fluent, confident, and correct use of the standard spoken form of one’s native language. It also established a standard where students’ abilities are developed within an integrated program of speaking and listening, reading and writing. Recent studies also equate oracy with the notion of “talking to learn” within the perspective that knowledge is constructed by the individual knower, through an interaction between what is already known and new experience. An example of oracy-based education initiative was the UK’s National Oracy Project, which recognized the role played by classroom talk and put equal treatment between spoken and written modes. (Wikipedia)

In The Concept of Oracy (1970) Wilkinson says that, when asked to qualify ‘oracy’ in only three words, he defined it as the ‘verbalisation of experience’ – expressing our own experiences and ideas, but was never satisfied that covered all bases until he realised he could re-order the words: ‘the experience of verbalisation’ – listening to the experiences and ideas of others. I agree with him that the two definitions together paint the whole picture.

Listening is intrinsic to speaking – the two should never be separated conceptually. The child learns to speak through hearing speech, subject to speaking and listening ability:

- The more the parent/s or carers of a young child talk with that child, the more the child will talk.

- The wider the vocabulary that same adult uses, the wider the vocabulary the child understands and eventually uses.

- The more often a word is repeated in a range of contexts, the better the child will understand and embed it.

- If the adult who talks to the child for most or all of its first years, talks with a local accent, the child will talk with a local accent.

- If the adult talks in dialect, the child will talk in dialect.

- If the adult talks in Standard English (correct grammar and pronunciation) the child will talk in Standard English.

- If the adult talks in received pronunciation, the child will talk in received pronunciation.

- If the adult uses dialogic constructions in language, the child will use dialogic constructions.

These are facts, simple and clear. If we want children to be competent and confident speakers, presenters, writers and debaters, we MUST fill their lives with these models through constant exposure and active participation in oracy.

The ability to adapt speech for purpose is a strength, not a weakness. Being able to code switch into local accent or dialect is not a negative, as long as it is a choice and not the only form the individual has.

The English-Speaking Union was founded in 1918 by Sir Evelyn Wrench, with the aim of English-speaking democracies working together to build international fellowship and, ultimately, peace. It now devotes the majority of its work to developing young people’s skills of oracy in schools around the world. This organisation defines the skills of oracy as having four components:

- Reasoning and Evidence

- Organisation and Prioritisation

- Listening and Response

- Expression and Delivery

I found this inspirational; these are the skills of debate and presentation. THIS is oracy, the ability to not only speak, but to adapt speech, selecting and refining – and ultimately to write if that is the goal – for audience and purpose. Remember my historic maxim? If a child can’t say it, a child can’t write it. A reasoned argument for ‘A’ Level or for a Doctorate is seeded at the adult’s knee in the first seven years of life, and it blossoms (or not) and grows as that child moves through education.

In his letter to the Secretary of State, 30th September 2020, Robin Alexander (University of Cambridge: ‘Improving oracy and classroom talk in English schools: achievements and challenges’) presents six propositions:

-

We have known for a long time that talk is essential to children’s thinking and learning, and to their productive engagement in classroom life, especially in the early and primary years. We now have additional evidence, from over 20 major international studies, that high quality classroom talk raises standards in the core subjects as typically measured in national and international tests.

-

There can no longer be any doubt that oracy should feature prominently within the statutory national curriculum.

-

We need a different kind of talk from teachers in order to extend the repertoire of pupil talk and raise the standard and cognitive impact of classroom talk overall.

-

Though the terms ‘speaking and listening’ and ‘communication skills’ indicate objectives of indisputable educational significance, they have become devalued by casual use and should be replaced by terms that signal the emphatic step change in thinking and practice that is needed. ‘Oracy’ is a neologism which some find unappealing; ‘spoken language’ fits the bill reasonably well, though it doesn’t have the connotation of acquired skill that, by analogy with literacy, ‘oracy’ possesses.

-

There is a strong case for revisiting the 1975 Bullock Report’s advocacy of ‘language across the curriculum’ in order to underline the argument that educationally productive talk is the responsibility of all teachers, not just those who teach English.

-

Since this is about the quality of teaching as well as the content of the curriculum, it has implications not only for the NC review but also for initial teacher training, CPD, inspection and professional standards.

Alexander goes on to note that the ‘Cambridge Primary Review’ took the penultimate point further:

We recommend that in addition to the programmes of study of English, there should be a clear statement on language across the curriculum which requires attention in all subjects to the character, quality and uses of reading, writing, talk and ICT, and to the development of pupils’ understanding of the distinct registers, vocabularies and modes of discourse of each subject.

The Cambridge Dictionary defines oracy as:

the ability to speak clearly and grammatically correctly.

It is SO much more!

In my next blog I will exemplify one or two of the oracy activities I have seen embedded in lessons recently in schools.

Talk:Write

A fun and flexible approach to improving children’s vocabulary, speech, and writing.

Top Tips for Teaching Suave Words

Updated 01/09/2023

As so often happens, the more I watch children at work in the classroom on Talk:Write and the more I talk with talented teachers, the more examples and ideas for additional support spring to mind. It was this behaviour that led to the generation of over 900 quality resources that are already available on our free resources page, with new ones being added all the time. It is as a result of this constant stimulation and reflection that I am working on the Top Tips for Teaching Suave Words book. The book is available now from our shop.

From the launch of the suave word of the week, to the fun suave word champions sessions, this book has it all and is mainly written in short, bulleted tips for quick and easy access. Dip in to read about assemblies, EAL, effective use of time, teaching across the curriculum and gen-up on a range of quick-fire activities to embed your latest suave word. Because important points are repeated in different sections when still applicable, this book can be read from cover to cover to ensure you are not missing a trick, or the busy teacher can quickly access a particular aspect that they need more ideas or support with.

Schools already successfully embedding the system need not fear that goal posts have moved, but everyone will be excited by some of the enrichment that has been provided through this addition to the programme.

Top Tips for Teaching Suave Words

A handy book with advice and activities for the pro-active teaching of ambitious vocabulary.

Top Tip for Launching the Suave Word of the Week

One example is avoiding the use of a pronoun for a new suave word when first launching it, instead the teacher should constantly use the new word in full throughout discourse and embedding activities. For example, instead of saying something like:

“Our new suave word of the week is ‘muse’. This is a delightful word and you will find you can use it in many subjects, both in speaking and in writing. Here is an example of how I have used it in a sentence. Please tell your friend what you think it may mean.”

The teacher may instead say:

“Our new suave word of the week is ‘muse’. Muse is a delightful word and you will find you can use muse in many subjects, both in speaking and in writing. Here is an example of how I have used muse in a sentence. Please tell your friend what you think muse may mean:

‘I was musing about the life of the baby lambs in the snow on the moors.’

“Now, what do you think muse might mean? That’s a very good guess. It means to think about or to reflect. Well done. Now, quick as a flash, spell muse. And spell muse again. And spell muse again. Well done everyone. Now I would love to hear you all using muse in your talk or see you use it in your writing.”

This constant repetition of the word would not be considered good practice in normal speech or writing, but because the teacher wants to embed the new word for all children, the constant re-use is a deliberate ploy that really is effective.

Suave Word Champions

Another great tip from the new book is the suave word champions. On the last day of the school week, each class has an internal contest. This may only take about ten to fifteen minutes at the start or close of an English lesson or between any other two lessons, and is mainly played through ‘fastest shout first’. The teacher will suddenly fire the suave word of the week at a small cluster of pupils and they all have to shout the spelling back. The fastest to complete scores a point. This is then repeated for the definition and for the use of the word in a made-up sentence. The child or children winning the most points is the class suave word champion of the week. We have a selection of four certificates available to download from the free resources page.

Suave Word Assembly

The climax is reached the following week in the suave word assembly. This assembly usually opens with a rapid ‘fastest shout first’ review of the past few week’s suave words with their spellings and meanings. The new suave word of the week is then introduced and the meaning given with an illustration of its use. The final celebration of the assembly is the suave word champions of the week, when the class winners of the previous week play off against each other to find the school suave word champion of the Key Stage for the week. There is a free suave word assembly resource on the free resources page.

In the Staffroom

One of the fun comments we have received from headteachers during this whole launch has been that, not only are children rapidly expanding their knowledge and use of enriched vocabulary – but so are many of the staff and there is frequently great laughter in the staff room as teachers vie to use the most new suave words of the week in discussions and chat as they go about their daily business!

What a privilege to work with our amazing profession!

Talk:Write

A fun and flexible approach to improving children’s vocabulary, speech, and writing.

A Ray of Hope

What a year! Schools and teachers everywhere have done such a great job in the face of so many repeated crises and every member of the profession must be exhausted and so much in need of the summer break.

Of course, we can’t really think of it as one year – it has been one long continuation of the pandemic – two and a half years of closures and adaptations, home schooling, catch up and – most infuriatingly – blame of anyone for poor decisions, except those to blame. Right from the first closure in March 2020, teachers and children have been expected to cope with repeated changes in procedures and practices. That first year with the March to June closures followed by more from December into February 2021 was a huge period of stress for everyone.

And everyone I know followed the lockdown rules to the letter – unless they worked in Downing Street of course!

We shall never forget that first lockdown when the rules were so strict and I, like so many, saw nobody except my bubble – my daughter, her husband and their two children. Schools were not yet au fait with home schooling and parents were very much on their own in a strange new world. Soon my grandchildren’s school were sending through maths and English activities for parental supervision and the mornings – including a P.E. session – were more or less sorted. By request, I took over the afternoons, with a mix of science, history, geography, art and ‘stuff’. No resources – where would we have been without the internet?

But we are privileged – we all three had the good fortune of higher education – all are in professions and with me being a teacher as well. What of the millions of deprived children suffering hunger and a restrictive environment – many without even a small garden to play in – and with parents who were themselves educationally deprived and so scarcely able to support their children in any meaningful educational ways? Coping with that first long lockdown of four months must have been a nightmare.

For ours, lockdown learning had some benefits. As a direct consequence, my grandson was the only eight year old in year four to be able to name the five oceans and seven continents at the start of a later unit about The Earth, and my 11-year-old granddaughter was the only one in year six to know the name of the capital city of Australia. What fun we had had playing ‘fastest first to find’ in Gammy’s (yes – that IS what they call me) two huge atlases! Geography on the hoof…

By the end of April 2021, however, the novelty had long worn off and signs of child stress were evident. Having no company their own age and being confined to house and garden took their toll and the last month of that first lockdown was a source of stress for all of us. But what if we had lived as part of a large family on the 13th floor of a multi-storey in a deprived location with no outside access?

This last academic year was mainly uninterrupted, schooling wise. Even the much loathed school bubbles had disappeared and despite several panics, not one lockdown was imposed on schools. Staff were valiant, covering and collaborating as covid spread, always seeking to keep life as normal and productive for children as they could, and the dreadful memories quickly began to fade. That’s the miracle of children’s brains! Time travels so very slowly – a year is a lifetime when you are in primary school. Can you remember how many years it seemed from one birthday to the next or from one festivity to the following one? That first, terrible year of the pandemic must have seemed to last forever for so many of our children. And yet unpleasant memories fade quickly if distracted by new and exciting experiences.

Today I accompanied my grandson (now 9) and my daughter on an inner-city ‘adventure’ to find ‘Football World’, where he was to attend a friend’s birthday party. My daughter and I were chatting as she drove, while my grandson was ‘busy’ on technology in the back seat. We were discussing the fact that everyone we knew had a cold, now at the start of July, all with a hacking cough, sneezing and a runny nose – but no-one felt poorly. That was when my daughter said that she had had a call that morning from her friend, who has ‘the cold’ – she had just tested positive for covid!

“Has covid gone away now?” my grandson piped up from the back seat – clearly that ‘one-ear-on-the-adult-chat’ policy was still in full force!

“No,” his mother told him, “but fewer people are getting ill now.”

When we got back to their house, I was tested. And I was positive! The radio news tells me it is probably the BA4 & BA5 variants that we have – highly infectious and fast moving but not causing illness for most. But this could morph again when the winter comes…

So, I am isolating – although I expect to be testing clear again in a day or two – and reflecting on the past two years and thinking about the future.

A time to reflect and review… a time to push harder for change and reform. The summary of the Times Education Commission, published mid-June, has given me such hope – I truly was beginning to despair that I would not see any improvement or significant change in my active lifetime within education, but at last the first buds of spring are showing.

As the commission says, ‘the way people shop, work, travel, bank and watch television has been utterly transformed over the past decade but schools have failed to keep pace. Instead of adapting to the 21st century, education remains stuck in the 20th and in some ways the 19th century.’

The 2nd lesson of the review describes the curriculum as ‘a narrow and rigid rubric that leaves no room for creativity.’ The progressive curricular models of so many other countries – some of which we, in our ignorance, would barely rate in terms of education – and of progressive schools in the UK, clearly far outstrip our national, historically knowledge-driven relic. Professor Dame Mary Beard is quoted as saying that the country has become ‘terribly snobbish’ about what education is for, adding: “It is still held back by class and privilege aspirations, which rank… [learning] …into what clever, posh white kids do, and what the other people do.”

The commission tells us that communication skills – ‘oracy’ in the jargon – should become mainstream in state schools, and that the independent sector has long understood the importance of the spoken as well as the written word.

The commission describes the huge ideological rift in the current curriculum as not being between left and right, but rather between knowledge and skills. ‘The national curriculum is described as being designed to introduce pupils to the best that has been thought and said rather than to help them to look to the future.’ The commission sees this as a false dichotomy, quoting Kevin Ellis as saying: “Education should be about both character and qualifications. It should open up pathways and support creative, inquisitive learners.”

How many of us have said similar over the past 40 or more years, to no avail? Throughout the 1990s and 2000s I, myself, designed many skill-driven curricular models for schools and organisations. These were all rooted in the English National Curriculum to allow for the pedants of Ofsted, but interpreted the required high knowledge content through investigation, communication, construction and analysis. Yet tradition dictated that – under pressure – many teachers cut back on the skills and reverted to teaching to the knowledge.

As the commission tells us, the next generation needs to be ‘…adaptable, inquisitive and empathetic.’ More than half the children who start school this next academic year will live to be 100. They will have to retrain many times over the course of their long careers…’

One hundred years ago from today fell between the world wars. The average life span was 54 years; Britain was recovering from the first world war and a global pandemic of 1918 to 1920 – the Spanish flu! The BBC began broadcasting in 1922 and by 1929 the first black and white television was being developed, as were fridges and crossword puzzles. The first commercial flights commenced and beach huts, bathing machines and Punch and Judy shows were all the rage at popular seaside resorts in England. The following decades saw the first telephones, computers and washing machines, yet 50 years later the 1970s were known as the decade of bell bottoms, discos and roaring inflation.

And from the commencement of my teaching career in 1965, I survived over 500 significant changes in education across Britain. My 57 years in education have been a constant of rethinking and re-skilling. Thus, I empathise so with the words of Tom Fletcher, principal of Hertford College in Oxford, when he says: “Those who adapt faster will win and those who adapt slowest will lose… This is about survival.”

It is my profound hope that this powerful report from the commission is the start of reform; that the pendulum of politics will cease to swing and great educationalists will take over the lead, bringing rational thought and the needs of the future to bear on the world of education and the curriculum.

Post script

And here we are… a few days after I completed this latest blog and once again the government is in shambles due to dishonesty and deceit, and we have another new Education Secretary! Much of this new blog may have read as controversial due to being inspired by, and often quoting from, the words of the Times Commission. Today is a sign of the times – we need change in how education policy and practice are decided – and we need it NOW!’

Talk:Write

A fun and flexible approach to improving children’s vocabulary, speech, and writing.

Be Word Wise

The following blog is one of a series linked to the Talk:Write programme to improve children’s oratory and writing.

The series includes:

Be the Speaker: improve children’s confidence, clarity, correct use of English and skills of oratory as a speaker. Aim: to enable all children to speak clearly, confidently and articulately in Standard English when required, and thus to influence the accuracy and style of their written work. Read Blog

Be the Teacher: empower children to correct their own and other’s grammar and pronunciation in speech, or grammar, spelling and punctuation in writing. Aim: to enable all children to recognise their own and other’s mistakes in written work and to edit or correct appropriately. Read Blog

Be Word Wise: enrich children’s vocabulary with a wide range of suave words that they know, understand, can spell and can use correctly in appropriate contexts. Aim: to expand children’s vocabulary significantly, including the use of words that are normally found in the speech or writing of a child of that age.

The contents of these three blogs complement each other and support each other in empowering pupils to be mature and articulate speakers and writers.

It was very gratifying to see the following synopsis yesterday, when I was due to write this blog to complete a series in support of our new programme, Talk:Write. My start had been slower than slow – inspiration being obstructed by a rash of proof reading and editorials – and suddenly here it was!

An article in the Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, Volume 8, 2015, Issue 3 entitled Efficacy of Rich Vocabulary Instruction in Fourth-and Fifth-Grade Classrooms summarising research conducted by Vadasy, Sanders and Logan Herrera of the University of Washington.

The trio conducted a randomised trial to test the effects of pro-actively teaching ambitious and exciting vocabulary to over 6,000 fourth and fifth grade pupils, comparing the impact to a similar number of children learning in ‘business as usual’ settings. Not surprisingly, the overall understanding and absorption of the words by pupils in the pro-actively taught set supports the application of pro-active teaching.

Since 1997, I have actively promoted the pro-active teaching of ambitious vocabulary in both primary and secondary schools. From 2000 to the present day, I have written, modelled and presented CPD on the importance of talk and vocabulary in improving children’s prowess as speakers and writers.

Step 1

Pro-actively teach a suave word each week throughout the school year. To facilitate this, we publish a set of free suave word resources each week in our free resources section and on Twitter (another of my passions!) for busy teachers to use if they wish. Most of our suave words are single syllable, yet still ambitious when used correctly. This enables a whole school to focus on the same word each week, meaning siblings can share suave word homework with each other and their parents or guardians, and one assembly a week can celebrate the word and play one or two of the games across the school.

There should be one suave word homework evening a week in a school. It is usually launched at the beginning of the week with the head or another leader introducing the word to the whole Key Stage or school during the assembly. The word would be displayed, explained and exemplar uses shared with the children. The words are carefully chosen to be accessible and achievable to all years in the school, making the homework discussion with family members much more attainable.

An example of a single syllable word might be ‘thrill’ or ‘angst’ while an accessible double-syllable one might be ‘headlong’ which is quite easy to learn and spell because it combines two known short words. We do offer a suave word of the week and supporting activities free on the website, however this programme is totally flexible and teachers may choose different words that they feel are more appropriate for their class or school, and may adapt games and activities to suit their classes. We also offer a ‘Suave Word Plus’ resource for children around 7 to 12, which involves learning more complex words.

‘Playing games’ with the children through a range of suave word activities is essential for embedding the word itself, its spelling, its meaning and its correct usage. Each game only takes a few minutes when the children are used to them, and they can be used as warm-ups before a lesson starts, as brain breaks within a lesson, or as ‘cool-downs’ at the end of a lesson. By applying the word appropriately in the context of any subject of the curriculum, the application and usage can be varied and flexible – and not dominate the English curriculum time.

At the start of the Talk:Write publication, I quote research that shows the importance of multiple exposures to new words, including meeting them and using them in a wide range of contexts. Although I have frequently said this myself and have advocated a multi-opportunity and cross-curricular approach to practising and embedding new language, I was surprised to read that – for many children – as many as 12 varied and relevant exposures may be needed to truly understand the different uses of the word in different contexts and to embed the word and its meaning/s in long-term memory.

Step 2

Enable children to work together in twos or threes to make up their own games and challenge one another, taking it in turns to ‘Be the Wise Word Leader’ and lead the activity. The most efficient approach is to give the whole class about ten minutes to make up around three different games on paper using suave words, before splitting the class into small groups. There is then no delay between turns, other than the copying of the next game onto the whiteboard. You can find the below games (except Suave Scramble) on our free resources page.

Suave Scramble is a very good option for this, the ‘teacher’ chooses one of the suave words the class has already learnt and re-orders the letters on a small whiteboard. They then show it to their partners who have to work out the word.

lidey = yield

Suave Spaces consists of making up simple sentences with a space in which one of their known suave words should be inserted. This is also a simple and effective game, providing the class are mature enough to do that without support.

The soldier was forced to _____________ to the King’s wishes. (yield)

Suave Select is based on Call My Bluff. The leader offers one suave word with three simple definitions and their partner or group have to shout out which is the correct definition.

thrill

To tickle someone

To excite someone

A pretty edge on a dress

Suave Sense gives three sentences that each have the target suave word in, but only one is used correctly and the group need to spot the correct usage.

aspire

The bird landed on the aspire

She aspires to run in the Olympics

Dad aspired the supermarket in the rain

Suave Meaning Match is a fun game, especially for Key Stage 2. The ‘teacher’ lists three suave words down the left-hand side of the whiteboard (copied from their pre-prepared list) but puts the wrong meaning next to each. Their partners have to shout out the correct meaning or join the correct pairs.

yield extremely fast

rapid the start of a river

source to give way

Step 3

Expect the children to start using their new suave words when appropriate, in their talk and presentations throughout their lessons and in any writing they do. For example, ‘angst’ would complement talk or writing about deforestation, climate change, floods, fire, volcanoes, war, extinction or a narrative such as a lost child. Initially, the teacher will prompt them to do this, but soon the children should take on this role themselves, asking the teacher and class which of their suave words would work well in this situation.

Children should clap or cheer when they hear one of their class use a suave word without prompting and also celebrate when they meet them in text. This may need to be prompted by the teacher at first – and taught through the teacher slipping one or two suave words into their taught input or explanations in a lesson – but it should soon become a spontaneous celebration that brings pleasure.

Parklands Primary School

At Parklands Primary School, where these approaches have been on trial in Years 6 and 3 since January, children are already getting highly excited when they hear someone use one of their suave words – or see them in text or a book they are reading. Using traditional tales and classics as the class reader is a big help in exciting the children, as they tend to be written in more mature language than some children’s books today.

Parklands Primary is located in one of the top 10% areas for deprivation, poverty and crime in the country, yet through a policy of love, rich experiences and curriculum enrichment children love their school, their teachers and their learning. Once a week, there is a Talk:Write assembly in Key Stage 2 which includes a celebration of children’s progress in writing, involves the children playing two or three of the games and introduces the suave word of the week, with its meaning and ways it might be used. Year 6 are also trialling the first public speaking exercise this term through writing their ‘Be the Speaker’ paragraphs on an aspect of the Victorians that each child chooses for themselves.

I have been amazed at how eager and enthusiastic the children have been to learn their new suave word of the week and to join in with the suave assembly. In Year 6, we have been introducing our own suave vocabulary weekly too and it has totally transformed our English lessons. The whole class have a greater understanding of complex vocabulary, they are able to explain the meaning of words in context, when reading our novels, and they are able to apply their suave words in their writing. The children are constantly striving to up-level their work and to include their newly learnt suave words. There is a renewed excitement, an enjoyment and a new-found passion for learning in English, which I am extremely grateful for.

Sam Rennison, AHT and Curriculum Lead

The use of suave words has been extremely effective in Year 3. The children have been learning two new suave words per week and are loving learning new, tricky words. They have been so excited when spotting suave words in books they are reading and have been making a real effort to use their new vocabulary in their writing. They have been keen to represent their class as the weekly suave word champion in assemblies.

Grace Huby, English Lead

How do children learn? How are they inspired? What makes a child want to write exciting vocabulary? Excitement does! Excitement to showcase their new skills in a fun environment. Rewarding the children by having an all singing and all dancing assembly, full of showcasing of all that they have learnt in front of the whole school. Talk:Write allows the children to speak the words, to express the words, to understand the words before implementing them in their writing. If you can’t talk it; you can’t write it. The suave assembly is to writing, oracy and English as the Times Tables Challenge is to maths. Simply awe and wonder!

Chris Dyson, Head Teacher

Talk:Write

A fun and flexible approach to improving children’s vocabulary, speech, and writing.

Be the Teacher

The following blog is one of a series linked to the Talk:Write Programme to improve children’s oratory and writing. The series includes:

Be the Speaker: improve children’s confidence, clarity, correct use of English and skills of oratory as a speaker.

Be the Teacher: empower children to correct their own and other’s grammar and pronunciation in speech, or grammar, spelling and punctuation in writing.

Be Word Wise: enrich children’s vocabulary with a wide range of suave words that they know, understand, can spell and can use correctly in appropriate contexts.

‘Be the Teacher’ is a simple, fun and effective way for children to achieve multiple exposures / opportunities to embed new language features or correct use of English in line with the research quoted in the ‘Talk:Write’ programme.

The aim of ‘Be the Teacher’ is for children to take on the role of the marker, proof-reader or audio-checker for their peer or peers, and behaving like a teacher through offering advice and corrections as necessary and when able.

This activity can be ‘played’ in several ways. All are fully adaptable and do not have to be pursued in exactly the same ways as described below. They can, also, be ‘played’ as stand alone activities in classes or schools not implementing the Talk:Write programme, however greater impact will be seen, and at much greater speed, when the programme is fully implemented.

- Be the Teacher: Spot the slips in Standard English during discussion and teaching within the class.

- Be the Teacher: Spot the slips in Standard English with pre-primed visitors to the classroom.

- Be the Teacher: Spot the slips in Bud’s writing.

- Be the Teacher: Spot the teacher’s slips in writing on the whiteboard working with your writing partner.

- Be the Teacher: Spot the slips in your writing partner’s work.

- Be the Teacher: Spot the slips on whiteboards or handouts.

1. Be the Teacher: Spot the Slips in Standard English Within the Class

I recommend this is the first ‘Be the Teacher’ activity to be introduced and that it should be launched as soon as the teacher starts to address the issues around all children speaking in Standard English.

The teacher should model some of the differences in sentence structure between Standard English and most strong accents or dialects. There are free resources for Talk:Write subscribers on the website that give many examples of the types of errors children need to watch out for when striving for Standard English, the most common being the noun/verb mismatches such as ‘we was’, ‘I were’ and ‘them are’.

I suggest that several times a week, the teacher should warn the children that they are going to intentionally make some mistakes as they talk. This could be in the introduction or conclusion of any lesson in any subject, so that the time taken to do this is subject-specific time. If the children think they have spotted a mistake they must shoot their hands up. The teacher will ask the first child to say what the mistake was and what the correct form should have been. If correct, the class will clap.

Children become very excited by this game and soon many hands will be shooting up in response to an error. This is the time when the teacher might suggest that the children could also deliberately make slips in their comments or answers, and the class will respond to these. At this point, it is useful to change the response from hands up and taking answers (which can take a lot of time up) to the class shouting out the correction. However, the teacher must prepare the class for this, instructing them on the need to shout in a friendly and supportive way. There must be no sneering or superiority in this activity. All children should experience the same respect.

2. Be the Teacher: Spot the Slips in Standard English with Visitors to the Classroom

The second step is to ask for members of the wider staff and older children to visit the classroom and give an oral message to the whole class, including a deliberate error in their spoken English. The class should call out the error with the same light-hearted positivity as they did between themselves.

It is important to note that, depending on the catchment area for the school, some members of the wider staff may naturally speak in a strong local accent. All staff should have been introduced to this activity previously, but it is important to protect staff from potential embarrassment.

3. Be the Teacher: Spot the Slips in Bud’s Writing

Bud is a fictitious member of every class. Teachers may wish to explain him as ‘an imaginary friend’. A teacher might name their class’s imaginary friend by any name they wished, providing there is unlikely to ever be a boy of that name in the school. It is usual to have a male imaginary friend as he can both protect the boys, who often tend to make the most small slips early in the process, and he can exemplify wonderful phraseology coming from a boy. His errors usually represent the errors the teacher has seen or heard being made by pupils in the lessons. Thus, use of Bud protects the self-esteem of pupils in the class.

The following is the procedure for using Bud in teaching Standard English:

- Have an empty chair at the front of the classroom for Bud, and talk to him from time to time, or ask him a question and pretend he has answered.

- A day or two after the class have done some written work – it may be only a paragraph in any curriculum subject at all – the teacher brings Bud’s paragraph to the class (written by themselves, of course) and puts it on the whiteboard. It will have some of the common errors in it and the children will work together in pairs to spot all the errors. The teacher will correct the errors on the whiteboard. Spelling and punctuation errors could also be included in this.

- In any lesson, in any subject, if no member of the class succeeds in spotting an error in oral input by the teacher or a child, or in written work on the whiteboard, Bud may appear to have spotted it and have ‘alerted’ the teacher.

- Occasionally, Bud may do a brilliant piece of work that illustrates recent points the teacher has been working on. The class will discuss his work in pairs and identify all its strengths.

4. Be the Teacher: Spot the Teacher’s Slips Working with Your Writing Partner

The teacher may now start making ‘mistakes’ when writing on the whiteboard. If the class fail to alert them, Bud (see item 3) may do so. The teacher corrects the mistakes as they are pointed out. If a mistake is not spotted the teacher may sometimes ignore it until later, and then ask the whole class to read the piece out loud together. They would be told there is a mistake they have not spotted. If the class still have not spotted the mistake, either Bud or the teacher will now announce it and correct it.

5. Be the Teacher: Spot the Slips in Your Writing Partner’s Work

At pre-planned points in the week, all children may occasionally be asked to write sentences or a short paragraph for their writing partner, with errors in the English deliberately included. The partners swap writing and identify and correct all the errors.

6. Be the Teacher: Sort the Slips on Whiteboards or Handouts

Occasionally, the children may be given a handout or an exercise on the whiteboard, with a range of sentences with errors for them to correct. The errors will be mainly in grammar but may also include spelling and punctuation.

The sentences may be about subject matter in any subject of the curriculum, so that the exercise comes out of that subject’s time budget.

Production of the corrected piece may be completed in pairs or alone, depending on the age and stage of understanding of the children, and may be done orally with feedback or on whiteboards or on paper.

Please remember – whatever the activity, all learning in Talk:Write should be fun and enjoyed in a positive, caring atmosphere. The above activities and ideas are aimed at supporting all pupils to be confident and accurate code switchers, being users of correct standard English when required, yet protecting their right to use of a personal accent, dialect or street talk when appropriate.

Talk:Write

A fun and flexible approach to improving children’s vocabulary, speech, and writing.